Sync DevContainer User With Your Host — Done Right (UID/GID + Username)

- December 8, 2025

- 11 min read

- Software platform

Table of Contents

If you ever worked with DevContainers, you probably hit the same wall everyone eventually hits: “Why are file permissions suddenly broken?”

It usually starts with something simple.

You create a file inside a DevContainer.

Then you jump to your host terminal, try to edit that file, and suddenly you’re fighting EACCES errors.

Or your Git repo shows files owned by root, even though you never touched sudo.

That pain kills flow. And the root cause is almost always the same:

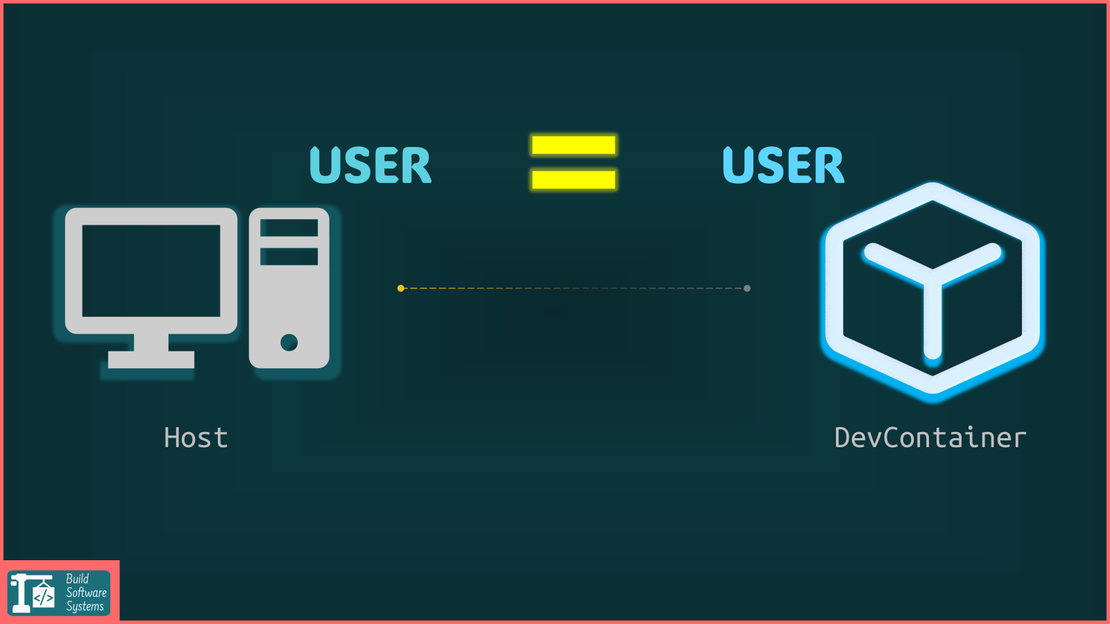

The DevContainer user doesn’t match the host user.

In this article, you’ll see exactly how to fix this, in a way that works with:

- ✔ any base image

- ✔ setups with or without a Dockerfile

- ✔ username sync optional

- ✔ UID/GID sync mandatory

- ✔ multi-user images

- ✔ preconfigured DevContainer images

You’ll learn the patterns that guarantee correct user synchronization every time. No hacks. No guesswork.

Info

Already familiar with DevContainer UID/GID issues?

The universal fix is to ensure your image contains exactly one regular user whose UID/GID and username is aligned by DevContainers.

Jump to the solution: Preferred Universal Approach (Base-Image Agnostic)

Why User Synchronization Matters (And Why It Breaks Things)

DevContainers look simple, but when the user inside doesn’t match your host user, you get issues like:

- Incorrect File Ownership: Files created in bind mounts or volumes by the container process are often owned by the host’s root user or a non-matching UID.

- Permission Denied Errors: This core issue blocks host-side operations, preventing your editor from saving files and build tools from modifying container-generated artifacts.

- Inconsistent CI/CD: Mismatched file permissions lead to local development behavior that doesn’t align with automated testing or deployment workflows.

Here’s a concrete failing example.

Example: Ubuntu 24.04 DevContainer Running as root

devcontainer.json:

1{

2 "image": "ubuntu:24.04"

3}

VS Code opens the container. The container runs as root by default.

Inside the container:

1touch test.txt

On the host:

1ls -l test.txt

2# -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Dec 8 07:00 test.txt

You cannot edit it normally from the host. Your editor may refuse to change the file. Git may warn you about “unsafe ownership”.

This is exactly why user sync matters.

The Two Things We Want

There are two independent goals:

- 1. UID/GID must match the host (mandatory)

- This is the real requirement. Without UID and GID equality, file permissions will break.

- 2. Username optionally matches the host (nice to have)

- Highly recommended, though optional. But if you want perfect symmetry—config files, shell prompts, SSH keys—then syncing the username helps.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.

How DevContainer User Settings Work

DevContainers define user behavior using:

remoteUsercontainerUserupdateRemoteUserUID/updateContainerUserID

(Documentation: https://containers.dev/implementors/json_reference/)

To make UID/GID syncing work:

- The user specified in

remoteUser/containerUsermust already exist in the image - That user must have a real home folder

- No other user in the image may have the same UID/GID as the host user, unless it’s the chosen dev user

- Then

updateContainerUserIDupdates that user’s UID/GID to match the host

If another user already has the same UID as the host, UID update becomes impossible.

Example of why UID clashes break things

Imagine an image contains two users:

| Username | UID |

|---|---|

| vscode | 1000 |

| bob | 1001 |

Your host user UID = 1000

Your host username = bob

If you set:

1{

2 // ...

3 "remoteUser": "bob",

4 "updateContainerUserID": true

5 // ...

6}

The DevContainer tries to set bob → UID 1000.

But vscode already has UID 1000.

Conflict.

The DevContainer runtime detects this assignment conflict and cannot proceed with the UID change for the target user.

The update fails.

Now your container user has UID 1001.

Your host has UID 1000.

Permissions break.

General Rule for Universal Reliability

To make UID/GID mapping always work, and optionally map the username:

You need exactly one regular (non-root, non-system) user in your image.

This user must be correctly configured:

- Explicitly set as the default DevContainer user. (This is the active configuration step that links the container to the runtime).

- Have a valid, configured home directory. (This ensures the user is functional and confirms existence).

- Be the only regular user defined in the image. (This strictly enforces the “one regular user” rule to avoid UID/GID conflicts).

Warning

Root stays root.

System users shouldn’t be modified.

System users like nobody often lack home folders.

If you want username sync too: That single regular user should have the same name as the host’s username.

This makes your setup:

- portable

- base-image-agnostic

- predictable

- conflict-free

Preferred Universal Approach (Base-Image Agnostic)

This is the method that works everywhere. It ensures:

- exactly one regular user

- user has host username

- UID/GID sync works

- clean home folder

- no multi-user clashes

- works no matter what the base image provides

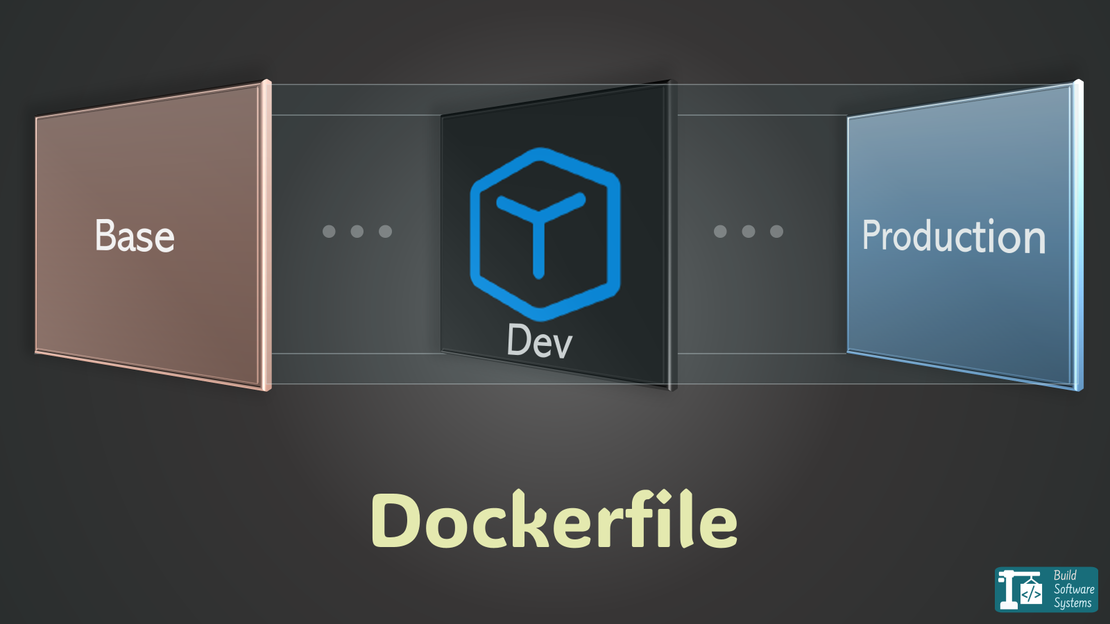

We implement this universal approach to cover the two possible setups:

-

Using a Dockerfile (e.g., when using a shared Dockerfile for dev + prod)

-

Not using a Dockerfile → use a local DevContainer Feature to create/sync the user. We cannot use lifecycle scripts because they do not change the image.

The main idea is to run the following script in the final devcontainer image build. USERNAME is the host username.

1#!/bin/bash

2set -e

3

4# Remove any existing regular user.

5# - the `getent` command lists all users

6# - the `awk` command filters regular users (UID >= 1000 and not "nobody")

7# - the `xargs` command deletes those users

8getent passwd \

9 | awk -F: '($3 >= 1000) && ($1 != "nobody") {print $1}' \

10 | xargs -r -n 1 userdel -r

11

12# Create the host matching user and add to sudoers and other necessary groups:

13# - username `USERNAME`

14# - UID 1000

15# - GID 1000

16# - gracefully skip if root

17if [ "${USERNAME}" != "root" ]; then

18 groupadd --gid 1000 ${USERNAME} || true \

19 && useradd -s /bin/bash -m -u 1000 -g 1000 ${USERNAME} \

20 && mkdir /etc/sudoers.d/ \

21 && echo "${USERNAME} ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" > /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME} \

22 && chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME}

23fi

Select the tab that matches your setup bellow.

- Using a Dockerfile

- No Dockerfile

Here is a visual representation of the directory structure:

project-root/

└── .devcontainer/

├── devcontainer.json

└── Dockerfile

In devcontainer.json:

1{

2 "build": {

3 "dockerfile": "Dockerfile",

4 "args": {

5 // Pass the host username as a build argument

6 "USERNAME": "${localEnv:USER}"

7 }

8 // ...

9 },

10 "remoteUser": "${localEnv:USER}",

11 "updateContainerUserID": true

12}

In your Dockerfile:

1#FROM ubuntu:24.04

2

3ARG USERNAME

4

5# Ensure all future commands run as root (necessary for user creation)

6USER root

7

8# Remove existing regular users if present

9RUN getent passwd \

10 | awk -F: '($3 >= 1000) && ($1 != "nobody") {print $1}' \

11 | xargs -r -n 1 userdel -r

12

13# Add host user (gracefully skip if root)

14RUN if [ "${USERNAME}" != "root" ]; then \

15 groupadd --gid 1000 ${USERNAME} || true \

16 && useradd -s /bin/bash -m -u 1000 -g 1000 ${USERNAME} \

17 && mkdir /etc/sudoers.d/ \

18 && echo "${USERNAME} ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" > /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME} \

19 && chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME} \

20 fi

Here is a visual representation of the directory structure:

project-root/

└── .devcontainer/

├── devcontainer.json

└── features

└── user-sync

├── devcontainer-feature.json

└── install.sh

Create a local Feature:

./.devcontainer/features/user-sync/devcontainer-feature.json:

1{

2 "name": "user-sync",

3 "id": "user-sync",

4 "version": "1.0.0",

5 "options": {

6 "username": {

7 "type": "string",

8 "description": "The username to create",

9 "default": "devuser"

10 }

11 },

12 // Make sure it runs after common utils, which can create new users too

13 "installsAfter": ["ghcr.io/devcontainers/features/common-utils"]

14}

./.devcontainer/features/user-sync/install.sh:

1#!/bin/bash

2set -e

3

4# Remove existing regular users if present

5getent passwd \

6 | awk -F: '($3 >= 1000) && ($1 != "nobody") {print $1}' \

7 | xargs -r -n 1 userdel -r

8

9# Add host user (gracefully skip if root)

10if [ "${USERNAME}" != "root" ]; then

11 groupadd --gid 1000 ${USERNAME} || true

12 useradd -s /bin/bash -m -u 1000 -g 1000 ${USERNAME}

13 mkdir /etc/sudoers.d/

14 echo "${USERNAME} ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" > /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME}

15 chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers.d/${USERNAME}

16fi

Then in devcontainer.json:

1{

2 //"image": "ubuntu:24.04",

3 "features": {

4 "./features/user-sync": {

5 // Pass the host username as a feature option

6 "username": "${localEnv:USER}"

7 }

8 },

9 "remoteUser": "${localEnv:USER}",

10 "updateContainerUserID": true,

11 // ...

12}

This guarantees a single regular user with the host username.

updateContainerUserID then aligns UID/GID automatically.

When You Don’t Need Full Sync (All Base Image Types)

Sometimes, you just need quick UID/GID synchronization without caring about the username matching.

Let’s walk through how this applies to different images.

1. Preconfigured DevContainer Images (mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers)

Example:

mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/base:ubuntu-22.04

These images already include one regular user, typically vscode.

So:

1{

2 "image": "mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/base:ubuntu-22.04",

3}

UID/GID syncing works out of the box.

2. Non-preconfigured Images

A. Image has exactly one regular user (ideal)

Example:

- image contains user

ubuntu - only one regular user

Then:

1{

2 "image": "ubuntu:24.04",

3 "remoteUser": "ubuntu",

4}

B. Image has multiple or no regular users

If the image has multiple regular users, there is a UID conflict risk. Hence, you must reduce to one regular user in the image. This requires modifying the image’s Dockerfile or build process.

If the image does not have any regular user, you must create one in the image. This is common with minimal images or distro bases and also requires modifying the image’s build process.

In both cases, because the image must be modified, it is recommended you use the preferred universal approach.

💡 Rationale: A new image build is required anyway. The universal script handles both user creation and excess user removal. This guarantees a consistent setup regardless of the base image used.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.

Conclusion

User synchronization in DevContainers looks simple, but gets messy fast when:

- base images contain multiple users

- UIDs clash

- root sneaks in as default user

- mounts cross the host boundary

- username mismatches break dotfiles or tools

The fix is always the same:

Ensure the image contains exactly one regular user, optionally named after the host username, then let DevContainers update its UID/GID.

Follow the Dockerfile or Feature method above, and you’ll never fight permission issues again—regardless of which Linux base image you choose.

Possible Issues / Clarifications to Keep in Mind

Before wrapping up, here are a few precise clarifications that are important when applying the methods in this article:

- 1.

updateContainerUserIDonly modifies ONE user: - It updates only the user defined in

remoteUser/containerUser.

If another user already has the same UID as the host, the update will fail. This is why the article insists on having exactly one regular user in the image. - 2. Root is never modified

- Root always keeps UID 0 and should not be the DevContainer user when you want host/UID sync (unless you use your computer as root — which you shouldn’t).

- 3. Don’t modify system users

- Many Linux base images include system users (sometimes with home directories).

Do not change their UID/GID — they are often tied to system services. Only manage the single regular dev user you create or designate. - 4.

remoteUsermust already exist remoteUser/containerUsermust refer to an existing user with a real home directory; DevContainers will not create them automatically.

These clarifications reinforce the key rule: one and only one regular user in the image is the foundation for predictable, portable user synchronization.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.