The 6 Fundamental Ways Users and Programs Interact Through the Terminal

- January 12, 2026

- 9 min read

- Programming concepts , Operating systems

Table of Contents

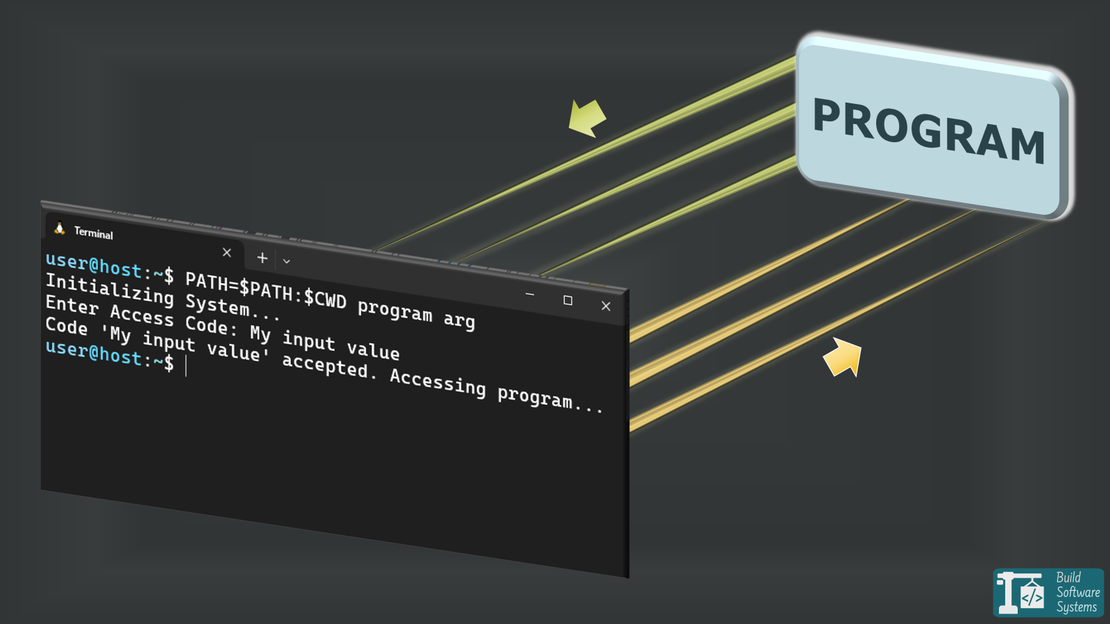

Every program communicates — it takes input and produces output. If you’re a beginner, the terminal can feel like a black box where things happen for reasons you don’t yet understand

But here’s the truth: in the terminal there are only six basic communication channels between a program and its user. Three let you talk to the program (Terminal → Program). Three let the program talk back (Program → Terminal).

Together, these explain how command-line programs communicate with the terminal: stdin, stdout, stderr, arguments, environment variables, and exit codes.

This article focuses on human-facing communication, not general inter-process communication like sockets or shared memory.

Once you understand them, programming becomes more mechanical than mysterious, and debugging stops feeling like guesswork.

We’ll walk through all six, show how Linux (bash) and Windows (PowerShell) handle them, and build a clear mental model with examples.

These concepts apply to any command-line interface (CLI), whether you’re using bash, zsh, or PowerShell.

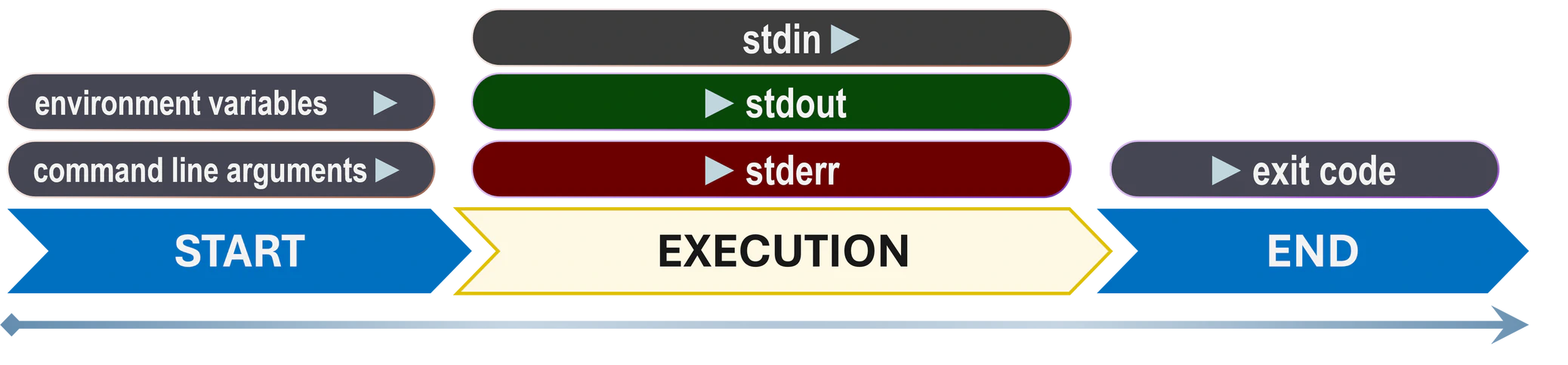

Static vs Dynamic Interactions

Before diving in, there’s one idea you need to have straight:

Static interactions happen once per execution.

You provide them before the program starts, and they stay the same for the whole run. And the program sends one final message after it ends (its exit code).

These are:

- Command-line arguments (user → program, only once at start)

- Environment variables (user → program, only once at start)

- Exit code (program → user, only once at the end)

Dynamic interactions happen while the program is running.

They allow back-and-forth communication.

These are:

- stdin (user → program)

- stdout (program → user, expected messages)

- stderr (program → user, unexpected messages)

All six are established by the operating system when a process is created; the terminal is just one possible endpoint.

1. Command-Line Arguments (Static Input)

Command-line arguments let the user tell something to the program once, right when it starts.

- Linux

- Windows

Linux (bash):

1user@host:~/$ ./greeter Alice

2Hello Alice!

Windows (PowerShell):

1PS C:\Users> .\greeter.exe Alice

2Hello Alice!

Those words after the program name are the arguments (here it’s Alice).

They’re meant for information the program needs up front to decide how it should run.

The program receives them before it begins running.

They’re copied into your process memory, typically as a list of strings, at startup.

This ties directly to what happens when an executable becomes a process. See my article on How a Program Binary Becomes a Running Process for reference.

From the program’s point of view, they’re fixed for the entire run.

Tip

Command-line arguments are perfect for optional modes, filenames, or quick user-provided values.

2. Environment Variables (Static Input)

Environment variables act like configuration knobs. They’re also passed to your program once—right when it starts.

You can set them like this:

- Linux

- Windows

Linux (bash):

1user@host:~/$ export NAME=Alice

2user@host:~/$ ./greeter

3Hello Alice!

Windows (PowerShell):

1PS C:\Users> $env:NAME="Alice"

2PS C:\Users> .\greeter.exe

3Hello Alice!

If you set a variable in the shell, it overrides whatever defaults the program would otherwise see. Your program sees exactly what the parent process hands it at startup.

Environment variables are inherited: a program receives a copy of its parent’s environment, not a shared one.

Arguments + environment variables form the full static input package.

Environment variables are typically used for broader configuration that many programs may share, while arguments are specific to a single invocation.

Note

In practice, environment variables are especially useful for values that rarely change on a given machine.

I’ve often used them to avoid long, repetitive command-line arguments for things like paths or credentials that are effectively part of a user’s setup.

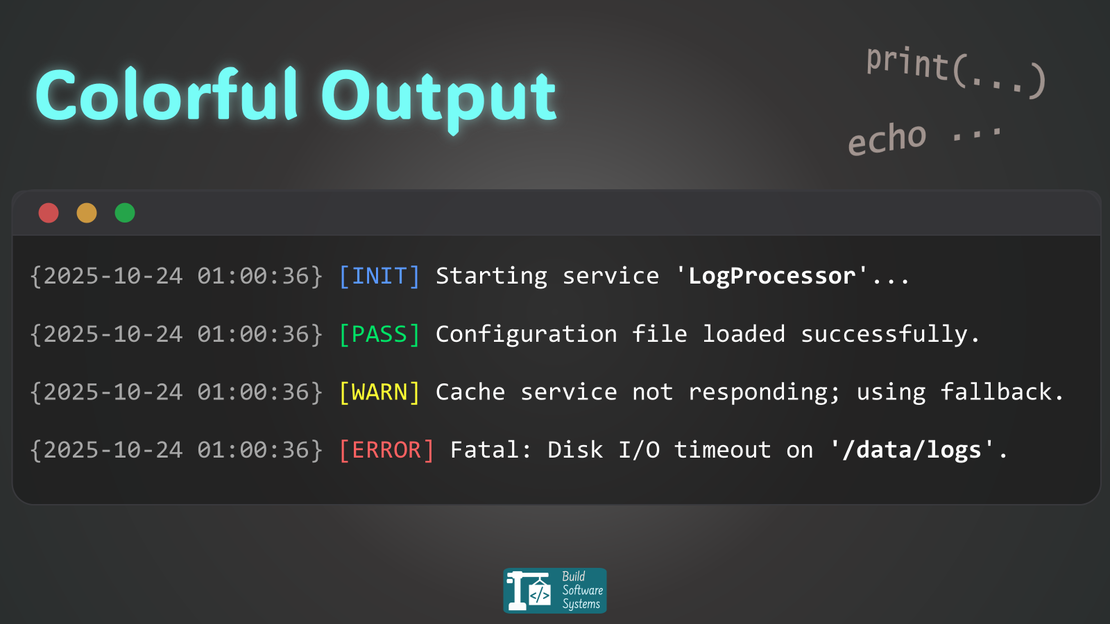

3. stdout – The Program’s Main Voice (Dynamic Output)

The standard output (stdout) is your program’s normal talking voice.

It typically prints expected information—results, messages, logs, prompts.

1user@host:~/$ find

2./.bash_logout

3./.bashrc

4./.bash_history

5./.gitconfig

But here’s the important bit: stdout is usually buffered, but the buffering strategy depends on what it’s connected to.

When stdout is connected to a terminal, it’s typically line-buffered.

That’s why printing a newline (\n) often makes text appear immediately.

Think of it like the Send button in a chat app: the message exists, but it doesn’t go anywhere until you send it.

When stdout is redirected to a file or a pipe, it behaves differently:

the program may collect larger chunks of text and write them out all at once.

That’s what “block buffered” means: output is saved up until the buffer fills.

This is a full internal buffer, not a newline or a single print call.

Until a flush happens, the text usually sits unsent in a buffer.

To write to stdout, the program must write to file descriptor 1.

On Windows, this is handled via STD_OUTPUT_HANDLE, though many environments emulate the standard 1 descriptor for cross-platform compatibility.

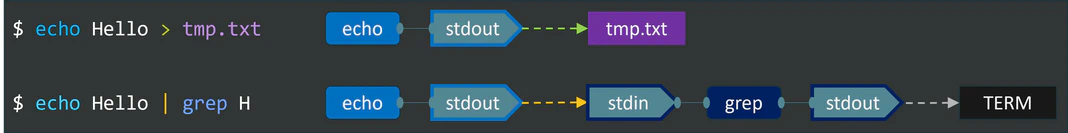

Tip

Pipes work by connecting one program’s stdout directly to another program’s stdin.

This is how complex command-line workflows are built from simple tools.

1cat file.txt | grep "search term"

Warning

I once lost time debugging a program because I printed an error message to stdout instead of stderr.

Since stdout was block buffered and never flushed before the program abruptly exited, the message never appeared at all.

Writing the same message to stderr made it show up immediately.

This is one of those bugs that only makes sense once you understand buffering.

4. stderr – The Program’s “Emergency Voice” (Dynamic Output)

The standard error (stderr) is meant for unexpected situations. Errors. Warnings. Anything “not part of the normal flow.”

1user@host:~/$ grep

2Usage: grep [OPTION]... PATTERNS [FILE]...

3Try 'grep --help' for more information.

By default, stderr is usually unbuffered or minimally buffered, which is why error messages often appear immediately even when output is delayed.

stdout and stderr are separate; the terminal just doesn’t know that

Both streams are different file descriptors (stdout is 1, stderr is 2); the same applies to Windows handles.

That separation lets you do things like:

1./program 1>output.txt 2>errors.txt

When a program starts, the shell usually connects both of them to the same terminal device.

By the time the text reaches the terminal, it’s just a stream of bytes.

The terminal receives only bytes; it doesn’t track whether they came from stdout or stderr.

Warning

When stdout and stderr both write to the terminal, their output may interleave in surprising ways.

On Windows, PowerShell exposes the same concepts, even though the underlying implementation and APIs differ.

Two voices, two channels, one screen.

Graphic User Interface (GUI) programs often have these streams too — they’re just not visible or connected to a terminal by default.

5. stdin – The Program’s Input Stream (Dynamic Input)

stdin is how your program receives information during execution.

From the operating system’s point of view, stdin is just a file descriptor like any other.

1user@host:~/$ read name

2BuildSoftwareSystems

3user@host:~/$ echo "My name is $name"

4My name is BuildSoftwareSystems

How terminal input actually reaches stdin

What you type in the terminal isn’t sent to the program until you press Enter.

Until then, the terminal keeps the text to itself.

Pressing Enter is the signal that hands the whole line to the program through stdin.

stdin is connected to file descriptor 0 (similar to the STD_INPUT_HANDLE on Windows)..

You can configure the terminal to send every keystroke instantly (keystroke/raw mode), but by default it waits for Enter.

Output buffering is controlled by the program’s output stream. Input buffering is controlled by the terminal.

stdin doesn’t have to come from a keyboard — it can also come from a file, a pipe, or another program.

More fundamentally, programs can read input and produce output at the same time because stdin is separate from stdout and stderr.

Info

Are stdin, stdout, and stderr only for terminals?

No. They are operating-system concepts that terminals commonly connect to, but any process can provide them when starting another program.

6. Exit Codes – The Program’s Final Message

When your program finishes, it returns a numeric exit code.

- On Unix-like systems, this is conventionally between 0 and 255.

- On Windows, native programs return 32-bit integers (much larger numbers), but this only works for native console apps (

.exe,.bat,.cmd).

It generally will not work for GUI apps (like Notepad) or built-in PowerShell cmdlets (likels).

This number is written into the process metadata (the Process Control Block, or PCB).

By convention:

0→ everything went well1→ something went wrong (simple general failure)- other values → your custom meanings

- Linux

- Windows

Check it in bash:

1user@host:~/$ true

2user@host:~/$ echo $?

30

Check it in PowerShell:

1PS C:\Users> whoami

2host\user

3PS C:\Users> echo $LASTEXITCODE

40

The shell captures it and makes it available via $? in Bash or $LASTEXITCODE in PowerShell.

It can also be captured programmatically by parent processes.

Info

On Windows PowerShell, for GUI apps (like Notepad) or built-in PowerShell cmdlets (like ls or Get-Item), use $? to check for success or failure instead.

This is the program’s last word before control returns to whoever started it (e.g.: the shell).

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.

How stdin, stdout, and stderr work together

Most command-line tools are small and simple because they don’t need to know about each other.

One program writes results to stdout, another reads them from stdin, and errors go to stderr.

Redirection and pipes let the shell wire these streams together, while exit codes tell the caller whether the whole chain succeeded or failed.

This design is why complex workflows can be built by combining tiny tools instead of writing one giant program.

Why You Care

1./build.sh > build.log 2>&1

2if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

3 echo "Build failed"

4fi

When automating tasks, you often want to separate normal output from errors.

Redirecting stdout and stderr lets you control what gets logged, what gets ignored, and what gets shown to users.

This separation is what allows tools to be combined reliably in scripts and pipelines.

Exit codes tie it all together. They let scripts and other programs know whether a command succeeded or failed, so they can react accordingly.

If you understand nothing else about the terminal, understand this:

- Automation, scripting, and tooling all depend on these channels.

- Every command-line program starts with these channels available, even if it never actively uses them.

Final Thoughts

If you grasp these six interactions, you understand the backbone of every command-line program—whether it’s written in C, Rust, Python, or anything else.

They’re simple, but they form a complete mental model of how humans and programs talk through the terminal.

Master them now, and you’ll understand not just what command-line programs do, but how they fit together.