Beyond the Port: How the OS Actually Binds and Connects

- February 16, 2026

- 8 min read

- Operating systems

Table of Contents

When I first started learning networking, I thought a ‘Port’ was just like a physical socket on the back of a server. You plug a process into Port 80, and that’s it—it’s “taken” — right? Not quite. The truth is far more interesting.

If you’ve ever wondered how a single server handles thousands of concurrent users, or how you can run multiple services on the same port number, you need to look closer.

Here’s the trick that trips up many developers: the secret isn’t the port itself — it’s the tuple. Understand this, and suddenly, everything about connections clicks.

This article explains how operating systems like Linux, Windows, and macOS manage TCP and UDP connections internally. It covers how port binding works, how IPv4 and IPv6 sockets differ, why multiple clients can share a single port, and why the 5-tuple defines a unique connection.

In Short

A TCP or UDP connection is uniquely identified by a 5-tuple: (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port, transport protocol).

A server can accept thousands of connections on the same port because each client has a different source IP and source port.

Port binding does not reserve a port globally — it reserves an (IP, port) combination within a specific address family.

The 5-Tuple: How Operating Systems Identify a TCP/UDP Connection

Your Operating System doesn’t track connections by port alone. It tracks them using a 5-tuple:

- Source IP

- Source Port

- Destination IP

- Destination Port

- Transport Protocol (TCP/UDP)

Here’s the key idea: the 5-tuple defines the connection. If any element differs, it represents a different flow.

Here’s what a typical ss -tan output looks like on Linux servers:

1user@host:~$ ss -tan

2State Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address:Port Peer Address:Port

3LISTEN 0 128 0.0.0.0:4821 0.0.0.0:*

4ESTAB 0 0 192.168.1.45:4821 198.51.100.12:55432

5ESTAB 0 0 192.168.1.45:4821 203.0.113.99:60111

6ESTAB 0 0 192.168.1.45:52331 203.0.113.88:9012

7user@host:~$

Focus on the highlighted lines. Both connections:

- Use the same destination port (

4821) - Target the same destination IP (

192.168.1.45) - Use the same transport protocol (TCP)

Yet they coexist without conflict. Why? Because their source IPs and source ports differ, making the full 5-tuple unique. The kernel does not see “port 4821”. It sees exact 5-tuples such as:

(198.51.100.12, 55432, 192.168.1.45, 4821, TCP)

(203.0.113.99, 60111, 192.168.1.45, 4821, TCP)

Different tuple → different connection.

Note

For TCP, the 5-tuple identifies a connection-oriented session.

For UDP, it identifies a flow — even though UDP itself is connectionless. The OS still uses the same tuple logic to demultiplex incoming packets to the correct socket.

Why Can Multiple Clients Connect to the Same Server Port?

Because a server doesn’t identify connections by port alone.

Even if thousands of clients connect to 203.0.113.10:443, each connection has a different:

- Source IP

- Source Port

Internally, they look like this:

198.51.100.8:60211 → 203.0.113.10:443 (TCP)192.0.2.44:49102 → 203.0.113.10:443 (TCP)203.0.113.77:51532 → 203.0.113.10:443 (TCP)

Same destination. Different tuple.

That’s why port 443 can serve millions of users at once.

Address Families Matter

The 5-tuple model applies to TCP and UDP sockets running over IP (IPv4 or IPv6).

Other address families, like Unix domain sockets (AF_UNIX), operate in a completely separate namespace.

Binding a socket to a file path (e.g., /tmp/socket.sock) does not interfere with TCP/UDP ports because AF_UNIX sockets use filesystem paths instead of IP addresses and ports.

IPv4 (AF_INET) and IPv6 (AF_INET6) are separate address families.

This means a service can often bind to a port on an IPv4 address independently of the same port on an IPv6 address, even if both addresses refer to the same machine.

Understanding address families helps prevent subtle bugs when mixing socket types — which becomes important in the next section.

Bind: Claiming Your Territory

When you “Bind,” you are telling the OS: “I want to listen for traffic arriving at this specific intersection.”

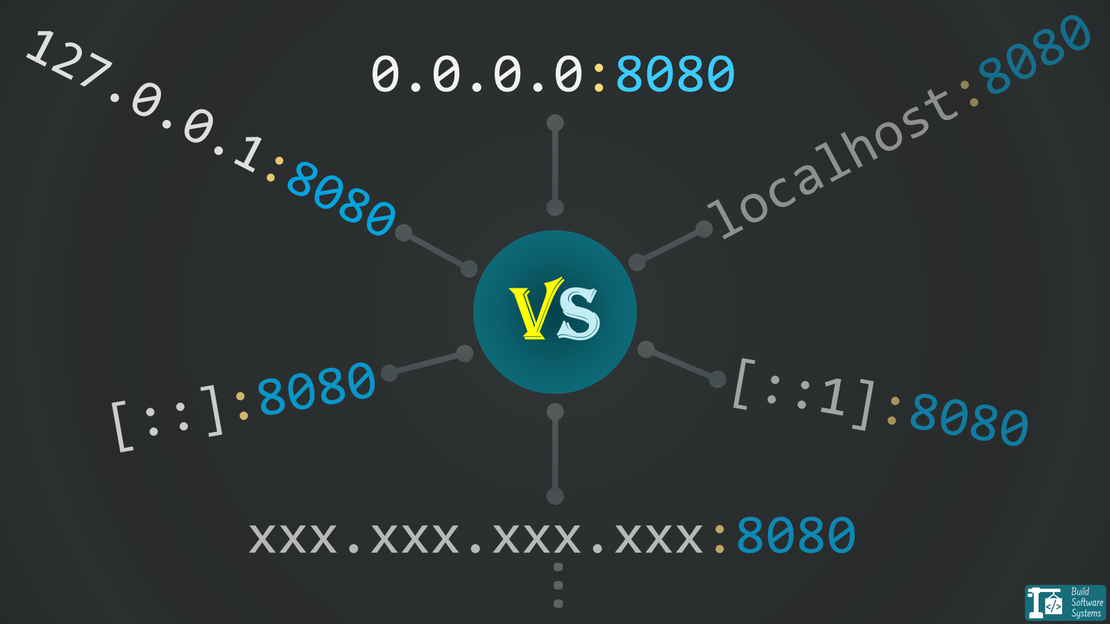

Many beginners bind to 0.0.0.0.

This is a meta-address (wildcard) that means “Listen on every available interface”.

While convenient, it’s greedy. It claims that port on your WiFi, your Ethernet, and your Loopback.

- IPv4:

0.0.0.0listens on all IPv4 interfaces. - IPv6: The equivalent wildcard (“bind-all”) address is

::, which listens on all IPv6 interfaces.

IPv6 adds one important detail: Dual-stack behavior (whether :: also accepts IPv4 connections) depends on the operating system and socket configuration.

For example:

- On Linux, an IPv6 socket bound to

::may also accept IPv4 connections via IPv4-mapped addresses (IPV6_V6ONLY=0by default). - On Windows and macOS, IPv6 sockets are IPv6-only by default (

IPV6_V6ONLY=1), so you need separate sockets for IPv4 (0.0.0.0) and IPv6 (::).

The reverse is not true: an IPv4 socket bound to 0.0.0.0 will never accept IPv6 traffic.

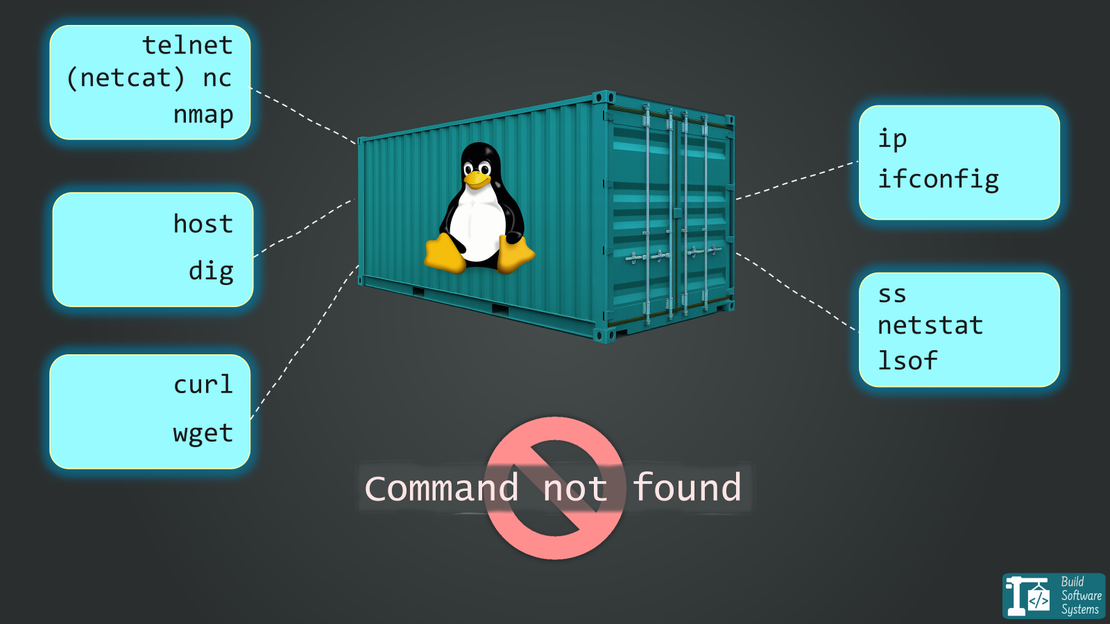

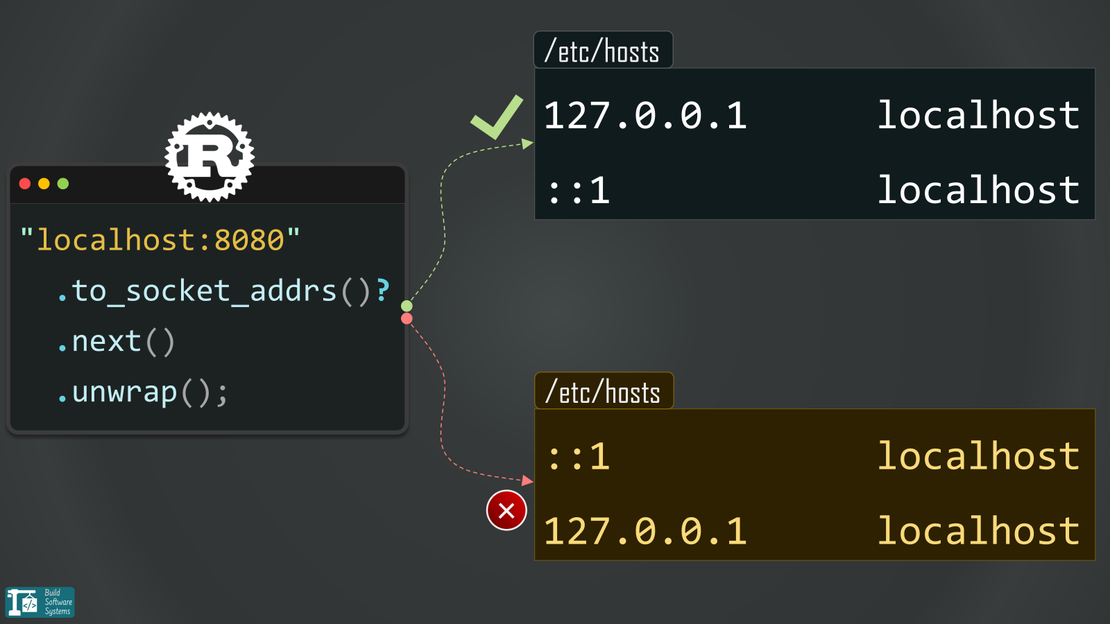

I ran into this when localhost resolved to ::1 but the server was bound to 0.0.0.0. Different address families — no connection. I documented the debugging process in this IPv4/IPv6 mismatch post.

Warning

Be careful about dual stack behavior when writing cross-platform network code. Assumptions about wildcard binding can lead to subtle bugs — or unintended exposure.

Subtle Behavior: Wildcard vs Specific Binding

If you bind a socket to a specific IP (for example 192.168.1.10:8080) and another socket to the wildcard address (0.0.0.0:8080), the specific binding takes precedence for traffic destined to that IP.

In other words:

- Traffic to

192.168.1.10:8080goes to the specifically bound socket. - Traffic to other local IPs on port

8080goes to the wildcard-bound socket.

The wildcard does not “override” specific bindings — it fills the gaps.

This behavior is part of how the kernel performs socket lookup and explains why binding conflicts sometimes behave differently than expected.

The Security Risk: Why 0.0.0.0 / :: is Dangerous

From experience, I’ve seen developers — myself included — accidentally expose services by binding to 0.0.0.0. It’s like leaving every door in your house wide open: convenient for testing, disastrous in production.

If your server has a public IP address, any service bound to 0.0.0.0 (IPv4) or :: (IPv6) is immediately reachable from the network — including the internet — if firewalls are not configured correctly.

The Golden Rule: Bind to the most restrictive IP possible.

- Local-only (Databases, internal APIs): Bind to

127.0.0.1— or any of the 16 million loopback addresses — (IPv4) or::1(IPv6 loopback). This ensures the service is physically unreachable from outside the machine. - Private Network: Bind to your internal LAN IP (e.g.,

10.0.0.5). - Public Web Servers: Bind deliberately — either to your public IP or to

0.0.0.0with proper firewall rules in place.

There are legitimate cases where binding to 0.0.0.0 (or ::) is necessary.

In containerized or orchestrated environments (for example, Kubernetes), IP addresses may be assigned dynamically.

A process often cannot know ahead of time which exact interface address it will receive.

In those cases, binding to the wildcard ensures the service listens on whatever IP the runtime assigns — while network policies and firewalls enforce exposure boundaries.

The important distinction is this: wildcard binding is not inherently insecure — uncontrolled exposure is.

By binding deliberately and combining it with proper network controls, you retain flexibility without sacrificing safety.

Connect: Reaching Out

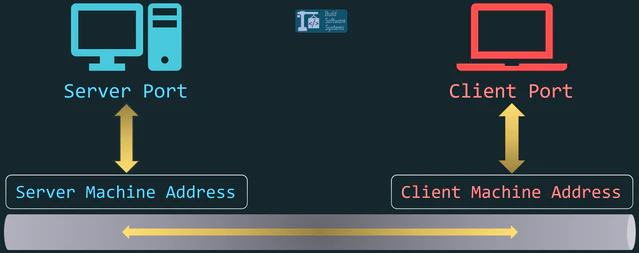

When your client (like a browser) calls “Connect”, the OS performs ephemeral port allocation.

You don’t usually pick your source port when connecting to a database. The OS picks a high-numbered source port from its ephemeral port range (for example, 32768–60999 on many Linux systems).

1user@host:~$ cat /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_local_port_range

232768 60999

3user@host:~/

That source port is what completes the 5-tuple and makes your outbound connection unique.

The flow:

- Client: “Connect to

1.2.3.4:80.” - OS: “I’ll use your local IP

192.168.1.5and local port49152.” - The Socket:

192.168.1.5:49152↔1.2.3.4:80

How the OS Handles the “Incoming”

When a packet hits your network card, the OS performs a lightning-fast lookup in its Socket Table:

- For established connections, it matches the full 5-tuple.

- For new TCP connections (SYN), it matches a listening socket by:

- Destination IP

- Destination Port

- Transport Protocol

- Address family

- If no exact IP match exists, it considers sockets bound to the wildcard address (

0.0.0.0or::). - If still nothing matches, it responds with a TCP RST (Connection Refused) or drops the packet (UDP, often resulting in an ICMP Port Unreachable).

Summary

If you remember just one thing from this post, let it be this: the OS doesn’t care about ports alone — it cares about the entire tuple.

- Bind is for listeners. It claims an (IP, Port) combination.

- Connect is for callers. It creates a unique path using an automatically assigned ephemeral source port, selected by the OS from its configured range.

- The Tuple is the law. Multiple connections can share the same destination IP and port — as long as the full 5-tuple is unique.

If this clarified something that used to feel confusing, I write deep dives like this regularly.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.

If You Want to Go Deeper

- Beej’s Guide to Network Programming — A practical, hands-on introduction to socket programming.

- RFC 793 (TCP) — The original specification that defines how TCP connections work.