Beyond 127.0.0.1: You Own 16 Million Loopback Addresses

- December 29, 2025

- 5 min read

- Operating systems

Table of Contents

Most local development starts the same way: you fire up a server and point your browser to localhost:8080 or 127.0.0.1:8080.

For years, I thought these were the same thing. I thought 127.0.0.1 was a single, static IP address reserved by the operating system for local traffic.

Then I hit a wall.

I was testing a distributed system. The program needed to connect to three different nodes. Each node expected to talk to a unique IP on Port 8080. On a single machine, you can’t bind three different processes to 127.0.0.1:8080. Port conflicts make this impossible.

I thought I needed Docker or three Virtual Machines. I was wrong.

The Best Kept Secret in Networking

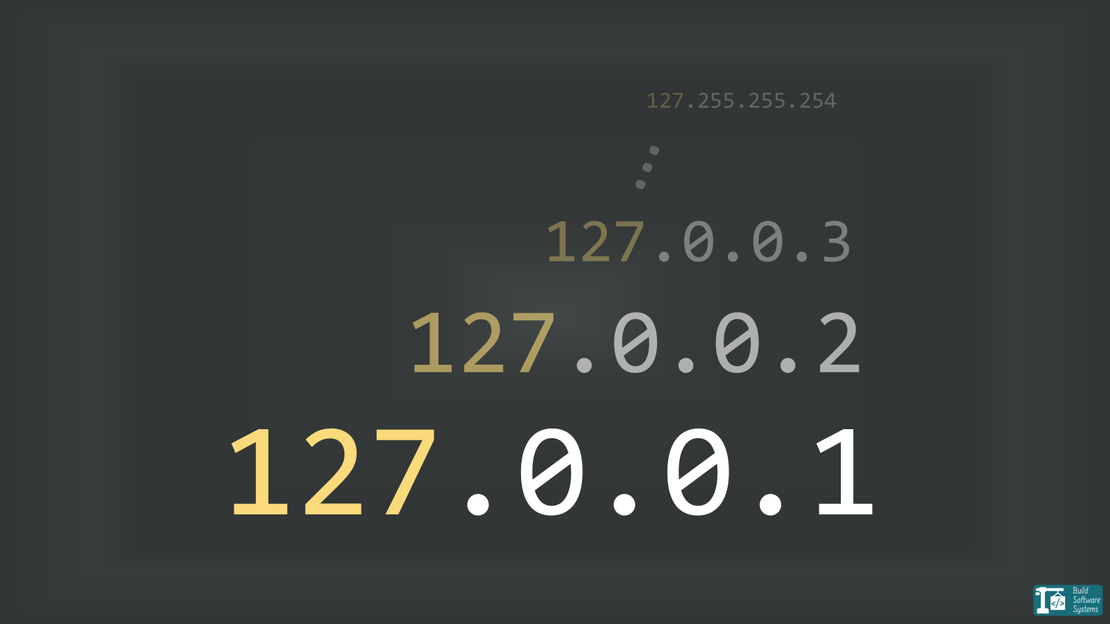

Your computer doesn’t just have one loopback address. If you are using IPv4, you own an entire /8 subnet.

According to RFC 1122, the entire 127.0.0.0/8 block is reserved for loopback. That isn’t just a few addresses. That is IP addresses that all point back to your local machine.

The first address (127.0.0.0) is reserved for network identification and the last (127.255.255.255) for broadcasting.

This leaves usable addresses. These allow your device to communicate with its own services without the data ever leaving the local network stack.

Try it yourself

You don’t need to configure anything. Your OS already knows this. Open your terminal and try to ping a random address in that range:

1$ ping 127.42.42.42

2PING 127.42.42.42 (127.42.42.42) 56(84) bytes of data.

364 bytes from 127.42.42.42: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.049 ms

464 bytes from 127.42.42.42: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.043 ms

564 bytes from 127.42.42.42: icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=0.036 ms

664 bytes from 127.42.42.42: icmp_seq=4 ttl=64 time=0.061 ms

It works. No setup. No configuration. Your traffic never leaves your network stack.

Note

On macOS, your system may not automatically route the entire range. If the test fails, you may need to manually alias the addresses to your loopback interface:

sudo ifconfig lo0 alias 127.42.42.42 up

Repeat this for each specific address you intend to use.

Why Should You Care? (The “Port Conflict” Fix)

In a standard networking setup, a “Socket” is the combination of an IP address and a Port number.

As I explained in my deep dive into how the OS handles Binds and Connections, the Operating System doesn’t just look at the port number to identify a connection. It looks at a “Tuple” of data. Because the IP is part of that unique identifier, changing the IP creates an entirely different socket in the eyes of the kernel.

If you bind a web server to 127.0.0.1:8080, that port is taken. If you try to launch a second server on 127.0.0.1:8080, you get the dreaded EADDRINUSE error.

But because you have 16 million addresses, you can do this:

- Service A: Bind to

127.0.0.1:8080 - Service B: Bind to

127.0.0.2:8080 - Service C: Bind to

127.0.0.3:8080

They all run on Port 8080. They all run on the same machine. They don’t collide.

Practical Example (Python3)

To see this in action, save this as server.py:

1from http.server import HTTPServer, BaseHTTPRequestHandler

2from threading import Thread

3

4def start(ip, msg):

5 class H(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

6 def do_GET(self):

7 self.send_response(200)

8 self.end_headers()

9 self.wfile.write(msg.encode())

10 log_message = lambda *a: None # Silences console logs

11

12 Thread(target=HTTPServer((ip, 8080), H).serve_forever).start()

13 print(f"Started: http://{ip}:8080")

14

15start('127.0.0.1', 'I am Node 1\n')

16start('127.0.0.2', 'I am Node 2\n')

How to test it

- Run the script in a terminal:

python server.py - Verify in a second terminal:

1$ curl http://127.0.0.1:8080

2I am Node 1

3

4$ curl http://127.0.0.2:8080

5I am Node 2

Why it works

The OS identifies a connection by the IP + Port combination. Since the IPs are different, the sockets are unique.

You can scale this up to the entire 127.0.0.0/8 range.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated.

The IPv6 Reality Check

We can’t talk about the future without mentioning IPv6.

In IPv6, the loopback address is strictly defined as ::1.

However, this doesn’t mean the “limitless” fun has to stop; it just means the strategy shifts.

While IPv4 has a pre-reserved block (127.0.0.0/8), IPv6 requires you to explicitly alias addresses from the Unique Local Address (ULA) range (starting with fd00::/8) to your loopback interface.

By manually assigning these “private” IPs to your local stack, you actually gain access to trillions of potential addresses, making your simulation environment even more powerful and future-proof.

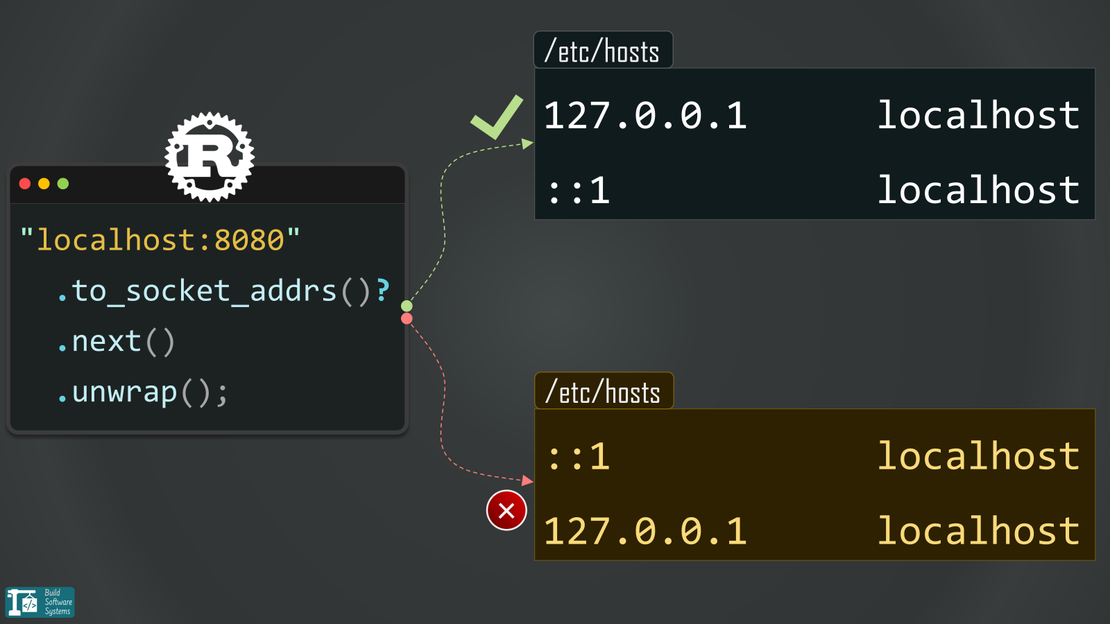

In fact, ignoring this shift is exactly how I ended up with a broken Rust application and an ‘Address family not supported’ error after a simple OS upgrade. When the OS starts prioritizing IPv6 but your code is hunting for an IPv4 loopback, things break fast.

Practical Applications

This networking behavior is particularly useful in the following scenarios:

- Microservice Development: You can simulate a production environment where each service has a unique IP address. This allows all services to use standard ports (like 80 or 443).

- Distributed Systems Testing: When testing consensus algorithms (such as Raft or Paxos), you can give each node a distinct identity without the overhead of multiple virtual machines.

- Local Identity Management: It simplifies local testing for applications that rely on source IP addresses for logic, such as rate limiting or IP-based access control.

Conclusion

Localhost is a name.

127.0.0.1 is just the first house in a very large neighborhood.

Don’t just use 127.0.0.1 because it’s the default.

Use Interface Aliasing to create as many local identities as your system needs.

Whether you are leveraging the legacy 127.0.0.0/8 block or configuring the modern fd00::/8 IPv6 range, you now have the tools to simulate complex, distributed environments on a single machine without the overhead of heavy virtualization.